Critical questions on the ivermectin meta-analysis

The methodological approach to the ivermectin meta-analysis provides further reassurance of the robustness of the findings. Mr Andrew Bryant and Dr Edmund Fordham describe some of the critical elements and the key findings of the study.

One feature of this study was the inclusion of preprints which have not undergone peer review. However, much of the criticism levelled at the inclusion of preprints is completely unfounded, argues Mr Bryant. “The inclusion of pre-prints and unpublished trials is something that is actively encouraged in Cochrane guidelines to safeguard against selective reporting of outcomes and minimise publication bias”, he explains. All the co-authors on the review were also well-qualified to ‘peer review’ anyway. Furthermore, requesting information from trialists can act as a kind of peer review process, but of greater importance is getting accurate details of outcomes, risks of bias and other important details, he adds.

Some people may have been surprised to see inclusion of a study by Lopez-Medina and colleagues that has been the subject of much controversy and calls for retraction. “It was easy to include the Lopez-Medina trial as, quite simply, it met the [pre-specified] inclusion criteria. If we had rejected it and not followed the protocol, we would have been open to criticism”, explains Mr Bryant. The inclusion of this trial did not ultimately budge the pooled results and it could be argued that, in some ways, it reflects a real-life situation where things do not always go according to plan.

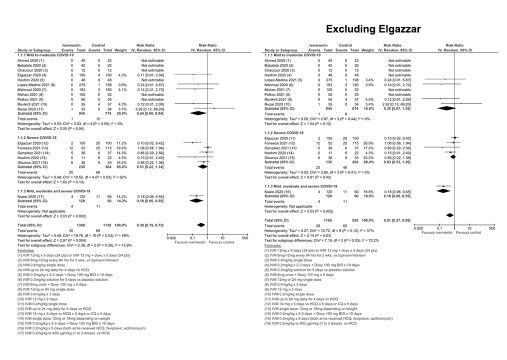

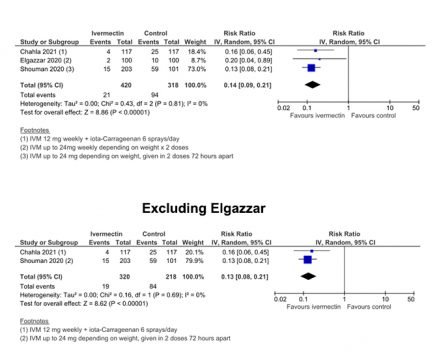

The results of the trial of ivermectin prophylaxis by Elgazzar and colleagues have been called into question in an article in The Guardian. The obvious question that arises is “If the Elgazzar results have to be removed – what difference does it make to the meta-analysis?”

The forest plot shows that the conclusions of the meta-analysis for mortality are robust and do not alter with the exclusion of the results from Elgazzar. The original pooled estimate (risk ratio for mortality) was 0.38 (95% CI = 0.19 – 0.73) and with the removal of the Elgazzar results 0.51 (95% CI = 0.27 – 0.95). “Instead of a 62% reduction in the point estimate for death it reduced to 49% with the exclusion of Elgazzar. So, ultimately, the conclusions are robust” says Mr Bryant.

Similarly, for prophylaxis, the original pooled estimate (risk ratio for infection) was 0.14 (95% CI = 0.09 – 0.21) and with the removal of the Elgazzar results 0.13 (0.08 – 0.21) this fell to 0.13. This would mean that the risk of being infected was reduced by 87% rather than 86%. “So the Elgazzar [results] had minimal impact in that analysis”, says Mr Bryant.

Whilst the removal of the Elgazzar results does not change the overall conclusions Mr Bryant emphasises that Prof Elgazzar has been contacted and says that he was not given the opportunity to answer his critics but is currently formulating a response. A correction to the Bryant-Lawrie review could be issued in the future, if necessary, depending on the outcome of investigations.

Trial sequential analysis and ‘moderate certainty’ evidence

The trial sequential analysis (TSA) undertaken as part of this review adds an extra dimension to the review. “It basically increased our confidence in the certainty of the evidence”, says Mr Bryant. A TSA is akin to a power calculation when designing a large primary trial and shows that there is sufficient power to detect a difference in an outcome, such as mortality, if one actually exists.

“So, in this case we can argue we already have sufficient numbers to give the answer and do not need any more trials”, he says. The TSA was not presented as a stand-alone analysis but to strengthen the ‘moderate certainty’ evidence judgement.

The term ‘moderate-certainty evidence’ can sound as if researchers are not sure whether there is an effect or not. “This is an important point – It is rather technical terminology and can often be misinterpreted by lay people who have never been involved in a systematic review”, says Mr Bryant. The term replaced the older term ‘quality of evidence’ as it has more to do with the confidence in the effect estimates (i.e. the exact size of the effect rather than whether there is an effect or not).

It’s worth noting that there are only four grades of certainty – the top grade is ‘high-certainty’ and ‘moderate’ is next level.

“In terms of the mortality outcome – the certainty of the evidence describes how much we believe the estimate of 62% reduction in mortality is. In this case there was moderate-certainty evidence, or the second highest judgement available. Given it is often very difficult to arrive at high certainty evidence, …..I’m convinced that there’s strong evidence that ivermectin is a favourable drug for covid 19”, concludes Mr Bryant.

Key messages

Dr Fordham says that the key messages that emerge from this work are:

- Covid-19 is a treatable disease, readily treatable at the outpatient stage using ivermectin amongst other simple medicines.

- Covid-19 is a preventable disease, using ivermectin and vitamin supplements, very cheaply, without needing vaccines that many parts of the world may simply not have or cannot afford.

“One thing that is absolutely clear about ivermectin and vitamins is that they cost virtually nothing”, he concludes.

Mr Andrew Bryant is a biostatistician and systematic review methodologist based at Newcastle University, in the Population Health Sciences Institute.

Dr Edmund Fordham is a physicist by training with extensive experience in the energy industry (check tape). He is also a long-term non-Hodgkin lymphoma survivor. He works with the Evidence-based Medicine Consultancy as a Consumer Representative.

Read and watch the full series on our website.