Advertisment

Altered movement of white blood cells may predict sepsis in patients with major burns

Tracking neutrophil motility patterns could provide early diagnosis of life-threatening condition. A team of investigators has identified what may be a biomarker predicting the development of the dangerous systemic infection sepsis in patients with serious burns. In their report in the open-access journal PLOS ONE, the researchers describe finding that the motion through a microfluidic device of the white blood cells called neutrophils is significantly altered two to three days before sepsis develops, a finding that may provide a critically needed method for early diagnosis.

“Neutrophils are the major white blood cell protecting us against infection, and a healthy individual has an army of 25 billion circulating neutrophils ready to fight invading pathogens,” explains Daniel Irimia, MD, PhD, associate director of the BioMEMS Resource Center in the MGH Department of Surgery and corresponding author of the PLOS ONE report. “The most common blood test ordered to evaluate a patient’s ability to fight infection is absolute neutrophil count, based on the assumption that – like well-trained soldiers – neutrophils are always fast, disciplined and effective in pursuing their targets, meaning that the size of the neutrophil ‘army’ is all that matters. Our work challenges that assumption and shows that, even when the number of neutrophils is unchanged, the army can fall into disarray and become ineffective.”

Sepsis is the leading cause of death among patients with major burns – those affecting more than 20 percent of body surface – with a mortality rate of 30 percent. It has been calculated that every 6 hours of delay in a sepsis diagnosis decreases the chances of survival by 10 percent. Since the symptoms of sepsis are similar to those of the systemic inflammation that occurs in almost every serious burn patient, diagnosing sepsis relies on culturing bacteria from the blood, a process that takes 12 to 24 hours.

While no previous studies had identified sepsis-associated changes in the motion of neutrophils – which travel to sites of infection in response to chemical signals – the motility or ability to move spontaneously of neutrophils is known to be less efficient in burn patients than in healthy individuals, leading the researchers to wonder whether correlations might exist between changes in neutrophil motility and sepsis in patients with major burns.

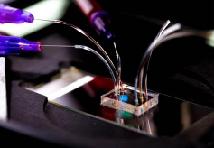

To investigate this possibility, the MGH team designed a microfluidic device with channels smaller than the diameter of neutrophils to study the cells’ motion toward a chemical signal. Straight channel sections measured the speed and persistence of the cells’ motion, and divisions and obstacles in the channels tested the cells’ ability to change directions. The researchers then analyzed the ability of neutrophils from blood samples of 13 patients with serious burns, collected several times during their treatment, to move through the device when it was primed with one of two chemical attractants or with saline solution, and compared it with the movement of cells from 3 healthy volunteers.

Neutrophils from healthy individuals moved quickly and efficiently through the device toward a chemical attractant – easily navigating around corners and posts – while cells from burn patients showed limited, slower and poorly organized movement toward the chemical signal. But analyzing movement patterns when the device contained no chemical attractant revealed a surprising finding: neutrophils from patients who had developed or were about to develop sepsis spontaneously moved through the device – like soldiers deciding to advance in the absence of any orders – while those from other patients and from healthy volunteers showed little or no motion.

This movement of neutrophils in the absence of chemical signals was observed in samples taken from some patients several days before a diagnosis of sepsis could be made, and once effective antibiotic treatment began, the unusual movement pattern began to fade. The authors note that, in addition to allowing faster initiation of antibiotic treatment, the ability to diagnose sepsis rapidly and accurately would reduce the inappropriate use of antibiotics that leads to the proliferation of resistant bacteria that is so common in burn units.

“Since only a handful of rare genetic disorders affect neutrophil function, it has long been assumed that studying these cells was not important; but our findings indicate that neutrophils play a much more important role in sepsis than has been appreciated,” says Irimia, an assistant professor of Surgery at Harvard Medical School. “Studies including larger numbers of patients with major burns and more precise measurements are under way. We’re also working to expand this investigation to other patients at risk for sepsis, to see if the findings from burn patients have broader application.”

For further information please click http://www.eurekalert.org/multimedia/pub/83701.php?from=284053

Contact: Terri Ogan

togan@partners.org