Advertisment

Making sense of EC guidance for safe management of hazardous medicinal products

Why some medicinal products can be hazardous

The European Commission Guidance for the safe management of hazardous medicinal products at work provides comprehensive instructions on how to handle hazardous medicinal products from identification to administration and even including laundry and wastewater management. In this series of short videos Paul Sessink – a member of the core team of authors – and Birgit Sessink – an experienced hospital pharmacist responsible for hazardous drug compounding at the University Hospitals of Leuven offer their insights into what the guidance tells us and how it works in practice.

Hazardous medicinal products (HMPs) are defined as those which are carcinogenic, mutagenic or reprotoxic. Some three-four million people are working with these drugs on a daily basis and there is growing concern that this could have adverse long-term health effects for them. The guidance document is detailed but it is only necessary for users to refer to the sections of the guidance that are relevant for their jobs.

The majority of hazardous drugs can be found in standard lists such as the NIOSH (National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health) list of hazardous drugs in healthcare settings and the European Trade Union Institute’s (2022) list of hazardous medicinal products.

What the EC guidance tells us about handling hazardous medicinal products

The European Commission guidance is not a law, although parts of the guidance are legal requirements in Europe, explains Dr Sessink. A good example of this is the obligation for an employer to provide information and training to employees who have to handle hazardous drugs in the course of their work.

The key steps in managing hazardous drugs are

- Identification of hazardous medicinal products

- Risk assessment of hazardous medicinal products

- Monitoring of exposure

- Repeat the above steps whenever necessary to stay up-to-date

Employees who handle hazardous drugs should receive appropriate training and this should be regularly updated or refreshed to ensure that personnel are up-to-date with new products and devices and have not developed bad habits.

How much contamination is too much in the workplace?

Working with hazardous medicinal products (HMPs) calls for safe systems of working to minimise the risks of occupational exposure for staff. However, monitoring of contamination must also be undertaken to check that systems are working,

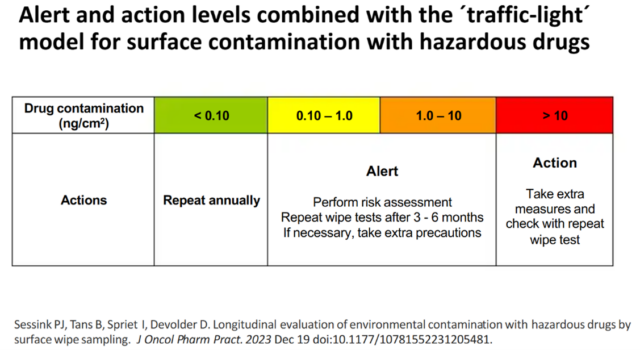

The most common risk for healthcare personnel is absorption of HMPs via the skin after contact with contaminated surfaces. Contamination with HMPs is measured by surface wipe testing and the results scan be interpreted using a ‘traffic lights’ model:

Measures to prevent contamination in the first place include the use of closed system transfer devices (CSTDs) and drug vials that have no exterior contamination when they arrive from the manufacturer. Staff who work with HMPs are protected by means of engineering controls, such as biohazard safety cabinets and CSTDs, to ensure that they do not come into contact with the drugs. In addition they wear personal protective equipment (PPE) comprising gowns, gloves etc.

How to make the EC guidance work in practice

At University Hospitals, Leuven the process for managing hazardous drugs from prescription to disposal is carefully controlled. At every stage, well-planned procedures minimise the risks of occupational exposure for the staff involved,

Compounded preparations are labelled in a distinctive way using labels with a yellow background and and additional ‘yellow hand’ label as a warning sign that it contains a hazardous drug.

Before they leave the pharmacy, compounded preparations are sealed in plastic over-wraps so that if there is a burst or breakage the drug is contained in the overwrap and does not contaminate a wider area.

Case study – responding to a large hazardous spillage

Even in the best systems things occasionally go wrong. Sometimes a whole series of events coincides and a serious incident occurs. Ms Tans describes how one such event occurred in December 2023.

A prescription was received for cisplatin 190 mg in 1000ml of 0.9% sodium chloride. When the injection was prepared the assistant forgot to remove 200 ml of fluid before adding the cisplatin, so the bag was over-filled, with a final volume of 1200ml instead of 1000 ml. The pharmacist released the bag after discussion with the doctor who confirmed that the extra volume was acceptable as people receiving cisplatin require extra fluids anyway. The infusion bag was covered with a yellow bag to protect the drug from light and then put into the protective over-package. However, the light-protecting bag was sealed together with the over-package and, in fact, the over-package bag was not sealed correctly or completely.

The preparation was required urgently on the ward and so a nurse came from the ward to collect it and carry it back to the ward. Under normal circumstances it would have been placed in a sealed box for transport to the ward. When the nurse reached the corridor outside the pharmacy the preparation fell out of the unsealed bag and burst, resulting in spillage of 1200 ml cisplatin solution. The nurse told the pharmacy department what had happened and then hurried back to the ward – with wet (contaminated) shoes – to take a shower and change her clothing. Pharmacy personnel took a spill kit to clean up the spillage. Because of the large volume of the spillage, additional spill kits had to be obtained. The spillage had occurred just before lunchtime in a busy corridor that leads to the staff restaurant so the task of preventing people from walking over the area and potentially spreading the drug further, was made more difficult. The cleaning department was asked to clean the whole area and the safety department was informed. It took almost two hours before the whole area was decontaminated, said Ms Tan.

As a result of this incident, some procedures were reviewed and refreshed and steps were taken to ensure that all staff were aware of the correct procedures to be followed.

About Birgit Tans and Paul Sessink

Birgit Tans is a hospital pharmacist at the University Hospitals of Leuven in Belgium. For the past 30 years she has specialised in compounding of cytotoxic drugs and is an expert on safe handling of hazardous drugs.

Paul Sessink first studied chemistry and later completed a PhD on hazardous drug exposure. In 1995 he founded the company, Exposure Control to provide services related to monitoring of hazardous drugs in the working environment. The company has provided services to about 350 hospitals in the world.

|

|

Read and watch the full series on our website or on YouTube.

This episode of ‘In Discussion With’ is also on Spotify. Listen to the full podcast now.